Search POM Topics

-

Crisis

-

General

-

Perioperative Medication Management

-

Investigations

-

Calculators

-

Cardiology

-

Complications

-

Day Surgery

-

Endocine

-

Haematology

-

Infectious Diseases

-

Neurology

-

Paediatrics

-

Pain

-

Respiratory

-

Useful Links

Overview of Antiplatelet Agents in the Perioperative Period

Broad Principles of Aspirin Management

- Patients taking aspirin for primary prevention should cease aspirin 7 days before their procedure.

- Patients with a history of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) should continue on aspirin, unless the associated bleeding risk outweighs a ~1 in 15 chance of death or non-fatal MI4.

- Patients on aspirin for cardiac risk reduction without a history of PCI should only continue aspirin if their perioperative cardiac risk is assessed as high and their risk of perioperative bleeding is small.

- Patients on aspirin as secondary protection against stroke should only continue if their perioperative risk of stroke is assessed as high, and their perioperative risk of bleeding is small.

Broad Principles of Clopidogrel Management

Patients on single antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel may be appropriate to substitute with aspirin from 7 days before their procedure.

Patients on Dual Antiplatelet Therapy generally have a strong indication for antiplatelet therapy. These patients should ideally have surgery delayed until their indicated period of DAPT is complete (6 months for PCI, 12 months for ACS) and should continue on aspirin through the perioperative period unless their planned surgery has a particularly high bleeding risk.

Aspirin as Primary Prophylaxis

NSAIDs and COX-2 Inhibitors

Non-selective NSAIDs may be continued for patients undergoing procedures at low risk of bleeding.

For patients undergoing procedures at high risk of bleeding, non-selective NSAIDs should be withheld for a period of 4-5 half-lives

|

NSAID |

4-5 Half Lives |

|

ibuprofen |

1 day |

|

diclofenac |

1 day |

|

indomethacin |

2 days |

|

naproxen |

4 days |

COX-2 inhibitors (celecoxib) do not significantly interfere with platelet activity and do not need to be withheld in the perioperative period.

Meloxicam has high selectivity for COX-2 and does not inhibit platelet aggregation or increase bleeding time6. It does not need to be withheld prior to surgery.ADP Inhibitors

Whether to interrupt ADP / P2Y12 Inhibitors is discussed in more detail below.

The 2022 ESC Guidelines advise the below durations to withhold these medications where withholding is appropriate.

|

ADP Inhibitors |

Duration to Withhold |

|

ticagrelor |

3-5 days |

|

clopidogrel |

5 days |

|

prasugrel |

7 days |

High Risk Groups

Aspirin in Patients at Elevated Cardiovascular Risk

Aspirin in Patients at Elevated Cardiovascular Risk (POISE-27)

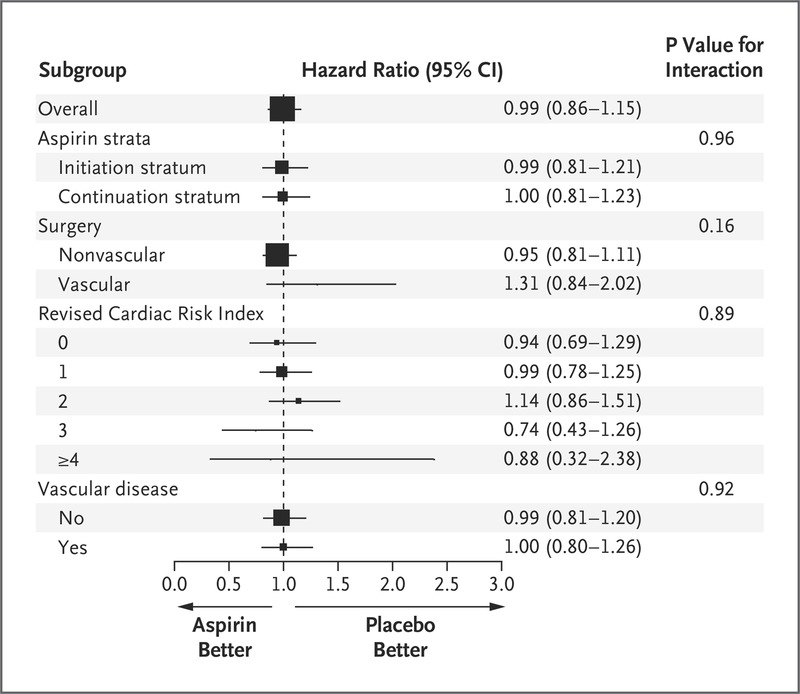

POISE-2 assessed the benefit of perioperative aspirin and clonidine in patients at increased cardiovascular risk.

Patients were randomized in a 2 x 2 factorial RCT to aspirin / placebo AND clonidine / placebo and followed for a range of outcomes including death, myocardial infarction and death at 30 days post op.

Aspirin use was not associated with any reduction in the rate of death or nonfatal MI (7.0 vs 7.1%, p 0.92), but was associated with an increased risk of major bleeding (4.6 vs 3.8%, p 0.04) but not life-threatening bleeding (1.7 vs 1.5%, p 0.26).

Life-threatening or major bleeding was shown itself to an independent predictor of myocardial infarction (HR 1.82 p < 0.001).

An interpretation of this result could be that the increased bleeding risk associated with perioperative aspirin use overshadowed any protection provided by the aspirin.

Poise-2 SubGroup Analysis for Primary Outcome of Death of non-fatal MI

|

POISE-2 Inclusion Criteria |

|

|

PLUS meet any of the following 5 criteria |

|

|

Selected EXCLUSION Criteria |

|

Aspirin in Patients Undergoing Vascular Surgery

POISE-2 demonstrated that patients undergoing vascular surgery are at increased risk of Major Adverse Cardiac Events (MACE) (~15% vs 6%), and that this risk was not significantly influenced by perioperative aspirin use8. Separate analyses of those patients undergoing surgery for vascular occlusive disease and aneurysmal disease also failed to demonstrate a significant aspirin effect in either group.

POISE-2 excluded carotid endarterectomy patients, who are presumed to benefit from continuation of aspirin9. A 2016 observational study found that patients continuing DAPT during CEA benefited from a 40% relative risk reduction in neurological complications, at a cost of increased risk of reoperation for bleeding10.

Aspirin in Patients with Coronary Stents

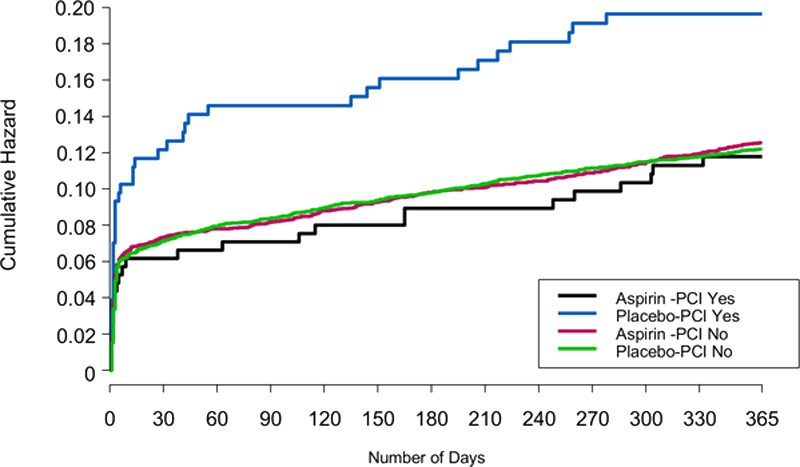

POISE-2 excluded patients who had received a Drug Eluting Stent (DES) within 1 year of randomization or a Bare Metal Stent (BMS) within 6 weeks of randomisation11.

Even after excluding those high risk patients, subgroup analysis of patients with any history of percutaneous coronary intervention showed that patients receiving aspirin had a clear reduction in risk of MI or death, persisting out to at least a year12.

Among patients with a history of PCI, around 14.5% had experienced death or non-fatal MI by one year post-op. Randomisation to aspirin resulted in an absolute risk reduction of 6.7% (NNT 15).

Patients with History of PCI:

Death or Myocardial Infarction at 365 Days

PATIENTS WITH ANY HISTORY OF PERCUTANEOUS CORONARY INTERVENTION SHOULD CONTINUE ASPIRIN THROUGH THE PERIOPERATIVE PERIOD WHERE POSSIBLE.

Coronary Stents Inserted Within the Past Year

Bare Metal Stents vs Drug Eluting Stents

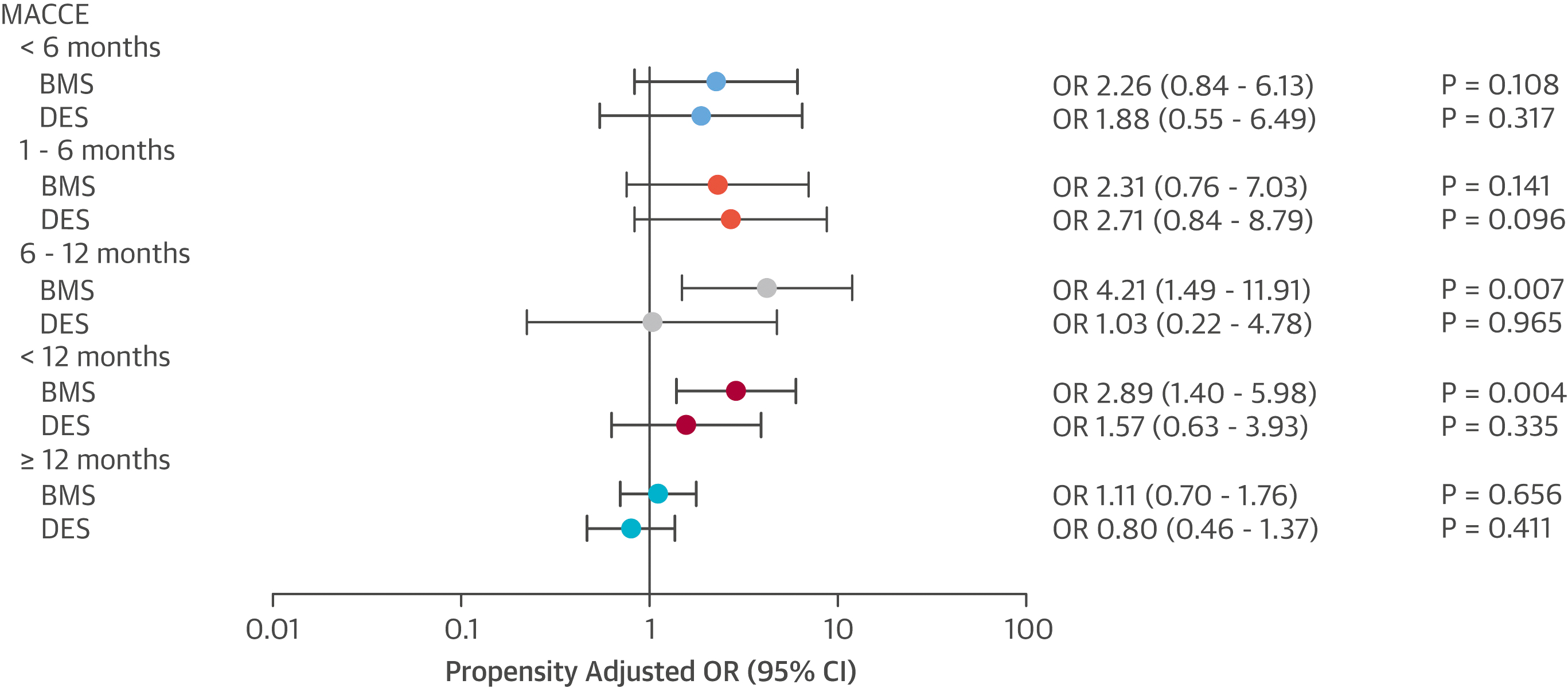

Earlier endothelialisation of BMS has traditionally thought to lower the risk of stent thrombosis, particularly where DAPT cannot be continued for an extended period. However, current generation DES appear to pose a lower risk of stent thrombosis than previous generations and newer evidence suggests that BMS do not present a lower risk than DES for patients undergoing surgery 6-12 months post stent insertion14.

The shrinking distinction between BMS and DES is reflected in the 2017 ESC guidelines17 which no longer draw as much distinction between stent types.

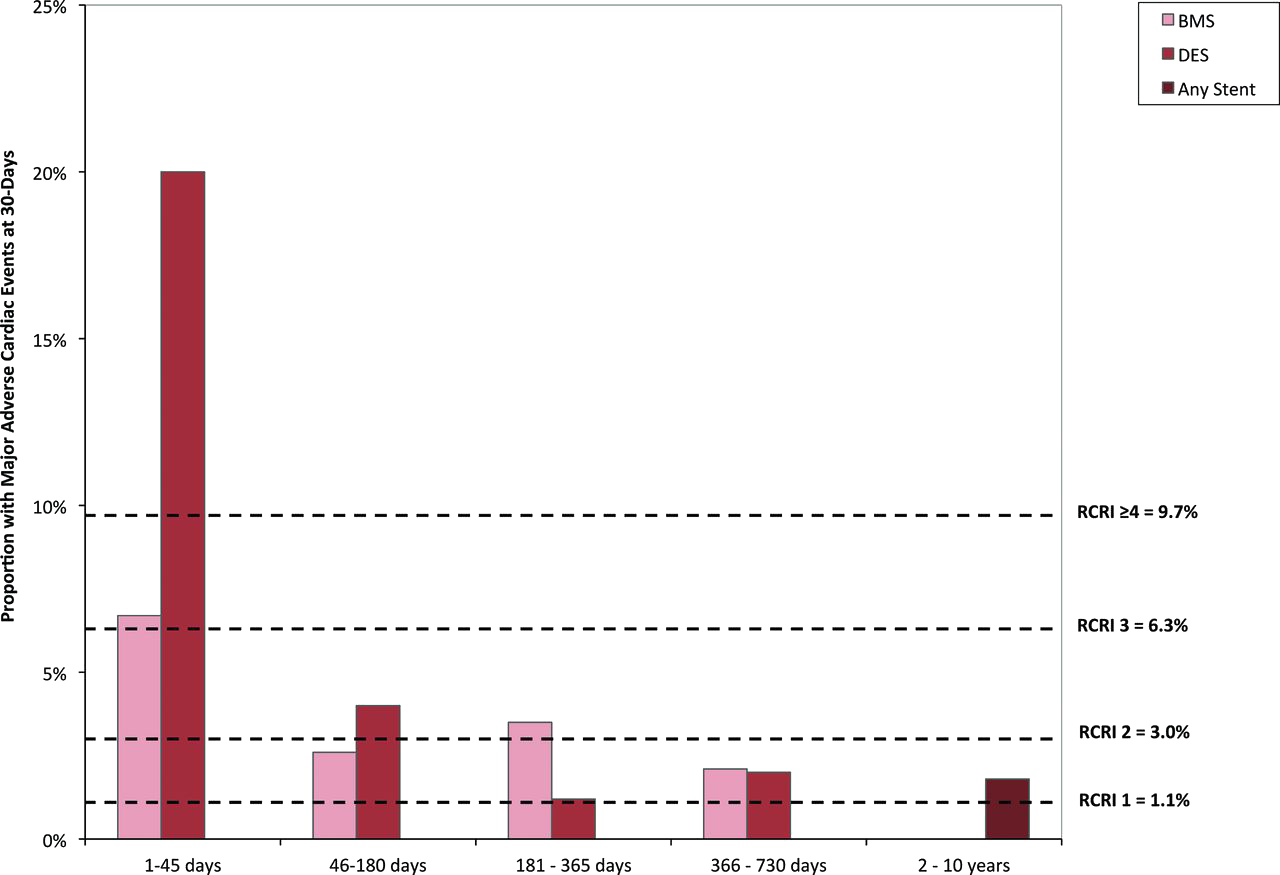

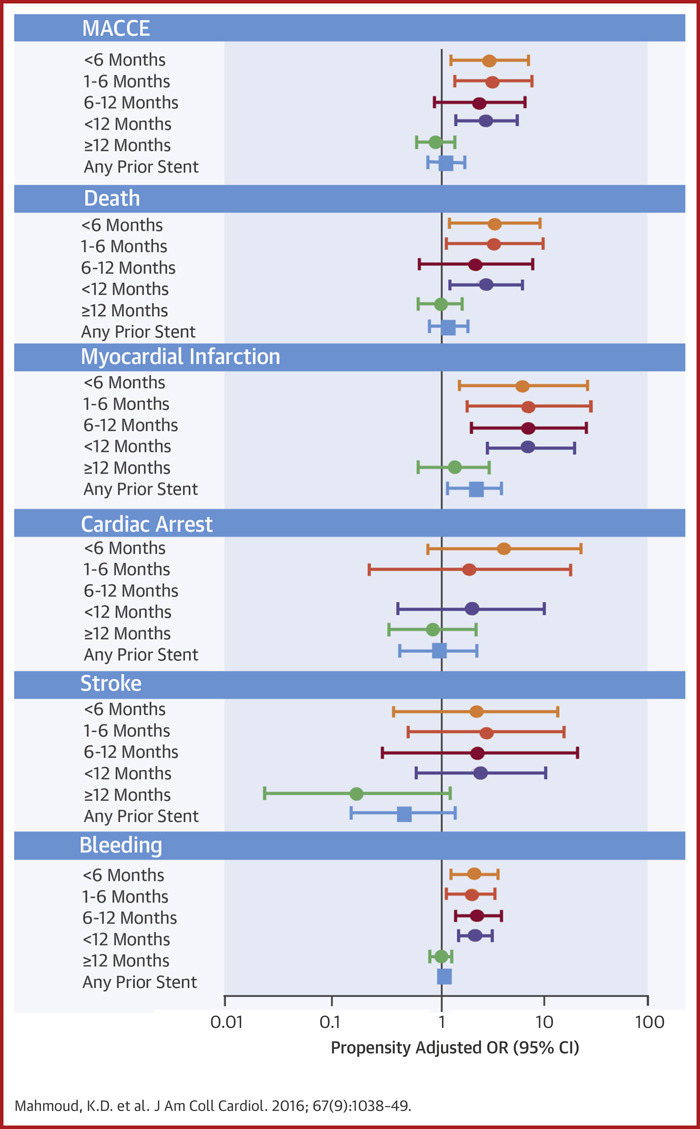

Risk of Perioperative Cardiovascular Events in Stented Patients, Stratified by Stent Type18.

Note that patients receiving a BMS were no safer than those with a DES

Proceeding to Surgery Early under DAPT Cover

Additionally, proceeding to surgery under DAPT is associated with an increased risk of major bleeding.

WHERE POSSIBLE, IT IS SAFER TO DELAY SURGERY UNTIL AFTER THE RECOMMENDED PERIOD OF DAPT IN COMPLETED, RATHER THAN PROCEEDING UNDER ANTIPLATELET COVER

Balancing Risk in Patients with Recent PCI

Where patients have undergone PCI in the 6 months before surgery, a careful balancing of their specific individual risks must be made. A multidisciplinary assessment of the consequences of proceeding vs delaying surgery, and continuing vs reducing vs interrupting antiplatelet therapy is appropriate, with the patient fully informed of the competing options. Whatever decision is made, these patients remain at increased risk generally, and require appropriately escalated monitoring.

|

Risk Considerations |

|

|

Risks of Delaying Surgery |

|

|

Risks of MACE |

|

|

Risks of Perioperative Bleeding |

|

|

Risk Considerations |

|

Risks of Delaying Surgery |

|

|

Risks of MACE |

|

|

Risks of Perioperative Bleeding |

|

Elapsed Time Since PCI

Time is the most important factor affecting perioperative risk. The first 4-6 weeks following PCI are associated with the highest level of risk, irrespective of stent type.

Acute Coronary Syndrome as the indication for PCI is next most significant risk factor to consider (see patient factors).

American guidelines21 allow for urgent surgery to be considered in patients with a BMS after a delay of a month, while acknowledging that the period of highest risk extends out to 4-6 weeks.

A 2010 Scottish study22 found surgery within 42 days of coronary stenting was associated with a higher rate of in perioperative in-hosptital death or ischaemic cardiac events than surgery performed beyond 42 days (42.4% vs 12.8%). Risks were even higher in patients revascularised for acute coronary syndrome (65% vs 32.%). No differences were seen between BMS and DES out to surgery 2 years post PCI.

A 2009 study23 found 14% of patients undergoing surgery within 30-90 days of PCI suffered MACE, even though most continued DAPT, whereas a 2016 matched cohort study24 suggested much of the additional risk beyond the first month post PCI may result from selection bias amongst patients requiring surgery in this period.

European Guidelines 25 allow for consideration of urgent surgery after a month in patients with both BMS and DES, although they are cautious in patients with high risk features (below), recommend 24/7 availability of a cardiac catheter lab and stipulate that aspirin must continue.

The American guidelines allow for consideration of urgent surgery in patients with DES after 3 months, provided the benefit outweighs the risk.

Both European and American Guidelines advise that, preferably, noncardiac surgery should be delayed at least 6 months after PCI.

Both European and American Guidelines advise DAPT should continue for 12 months following ACS. The risks and benefits of interrupting this period for surgery should be considered carefully.

Proportion of Patients With MACE* Within 30 Days After Elective Noncardiac Surgery Based on the Interval Between Most Recent Coronary Stent Insertion and Subsequent Noncardiac Surgery26

Horizontal dashed lines represent event rates for individuals who did not undergo coronary revascularization within 10 years before noncardiac surgery, as stratified by their Revised Cardiac Risk Index scores.

Risk of Coronary Stents in Non-Cardiac Surgery Stratified According to Time From Stenting to Noncardiac Surgery27

Reported Risk is relative to that of non stented control subjects.

For the first year following coronary stenting, risk of Major Adverse Cardiac and Cerebrovascular Events (MACCE), Death and MI are increased relative to that of unstented controls, whereas the risk becomes similar beyond year post stenting.

Patient and Stent Specific Factors

Stent thrombosis and MACE risk varies with individual patient and stent factors. Details of the patient’s PCI including the indication and specific treatment should be determined.

|

Risk Factors for In Stent Thrombosis |

|

|

Risk Factors for In Stent Thrombosis |

|

Patient Factors45 |

|

Acute coronary syndrome as the indication for PCI is associated with increased cardiac risk. ACC/AHA Guidelines recommend 12 months of DAPT following either BMS or DES insertion in setting of ACS 28.

|

Recommendation For Duration of DAPT in Patients With ACS Treated with PCI |

LOE* |

|

In patients with ACS (NSTE-ACS or STEMI) treated with DAPT after BMS or DES implantation, P2Y12 inhibitor therapy (clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor) should be given for at least 12 months |

I / B-NR |

|

In patients with ACS treated with DAPT after DES implantation who develop a high risk of bleeding (e.g., treatment with oral anticoagulant therapy), are at high risk of severe bleeding complication (e.g., major intracranial surgery), or develop significant overt bleeding, discontinuation of P2Y12 inhibitor therapy after 6 months may be reasonable |

IIb / A |

|

*Level of Evidence. Class I (Strong): Benefit >>> Risk. Class IIa (Moderate): Benefit >> Risk. Class IIb (Weak): Benefit ≥ Risk. Class III: Benefit = Risk. |

|

The patient’s cardiologist should be involved in consideration of the risk and benefits of urgent surgery requiring alteration of the prescribed antiplatelet regimen.

Perioperative Risk of Bleeding

The risks and consequences of perioperative bleeding for the specific planned procedure need to be discussed with the surgeon.

A stratification of perioperative haemorrhagic risk by surgery type is presented below.

|

Determination of Hemorrhagic Risk of Noncardiac and Cardiac Surgeries46 |

|||

|

Low Risk |

Intermediate Risk |

High Risk |

|

|

General, orthopedic, and urologic surgeries |

|

|

|

|

Vascular Surgery |

|

|

|

|

Cardiac Surgery |

|

|

|

|

Determination of Hemorrhagic Risk of Noncardiac and Cardiac Surgeries47 |

|

General, orthopedic, and urologic surgeries |

|

Low Risk |

|

|

Intermediate Risk |

|

|

High Risk |

|

|

Vascular Surgery |

|

Low Risk |

|

|

Intermediate Risk |

|

|

High Risk |

|

|

Cardiac Surgery |

|

Low Risk |

|

|

Intermediate Risk |

|

|

High Risk |

|

Randomisation to aspirin in POISE-229 was shown to be associated with an increased risk of major bleeding. Life Threatening or Major Bleeding occurred in 6.3% of patients taking aspirin and 5.2% of patients on placebo (Number Needed to Harm 88).

To assess when bleeding was most likely to occur, post-hoc analysis assessed risk of bleeding among as yet non-bleeding patients each day from the day of surgery until 30 days post-op. This can be interpreted as the additional bleeding risk attributable to aspirin were it to be commenced at each of these days post-operatively.

Risk of Life-Threatening or major bleeding with aspirin therapy

ie patients commencing aspirin on day 3 post-op suffered a 1% absolute increase in their risk of life-threatening or major bleeding

A 2018 meta-analysis of bleeding complications in patients on antiplatelets undergoing noncardiac surgery is available here.

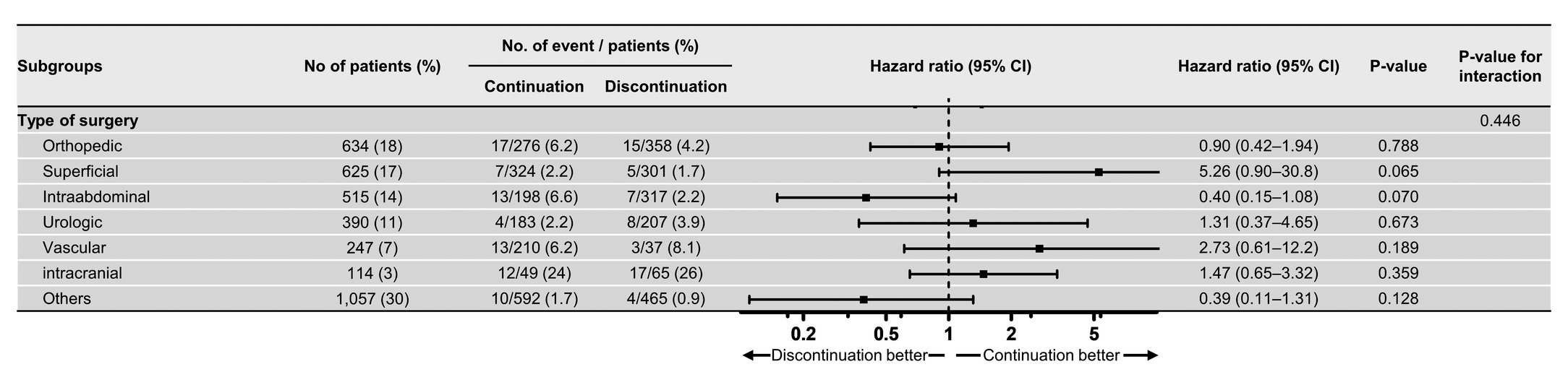

A retrospective study of 3582 patients undergoing NCS following second generation DES had their antiplatelet therapy continued or withheld according to physician preference, and assessed for 30 day occurrence of MACE, Major Bleeding and Net Adverse Clinical Effect (composite of death, MACE and major bleeding). No statistically significant differences were seen in any of these end points between continuation or interruption groups, but patients undergoing intraabdominal surgery were seen to do better with interruption of antiplatelet therapy30.

Adjusted Hazard Ratio for Net Adverse Clinical Effect (Death, MACE or Major Bleeding) in Patients with DES Continuing or Withholding Antiplatelet Therapy According to Physician Preference

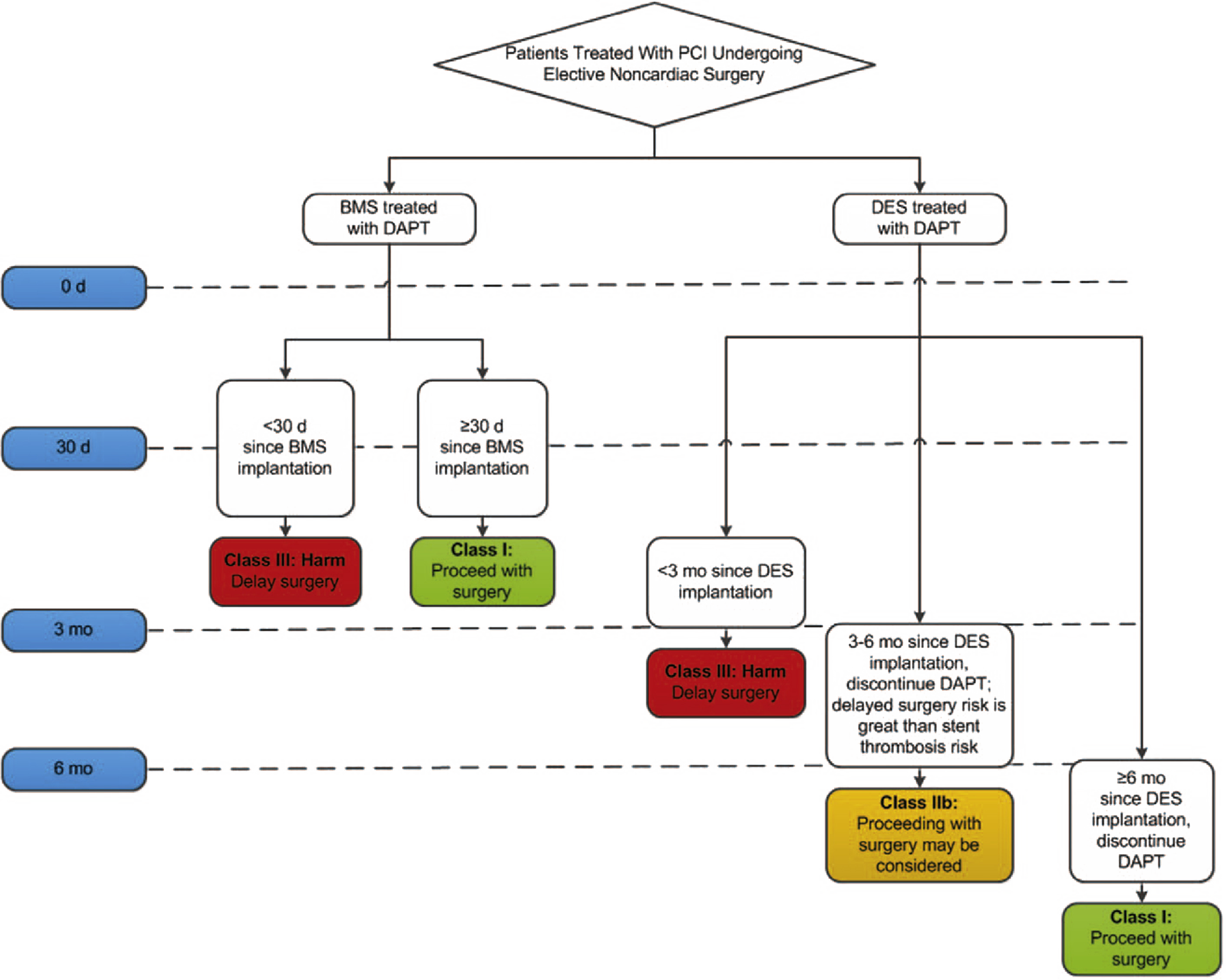

ACC/AHA Recommendations on DAPT in NCS (2016)

ACC/AHA Recommendations on DAPT in NCS (2016)31

|

Recommendation |

LOE* |

|

Elective noncardiac surgery should be delayed 30 days after BMS implantation and optimally 6 months after DES implantation. |

I / B-NR |

|

In patients treated with DAPT after coronary stent implantation who must undergo surgical procedures that mandate the discontinuation of P2Y12 inhibitor therapy, it is recommended that aspirin be continued if possible and the P2Y12 platelet receptor inhibitor be restarted as soon as possible after surgery. |

I / C-EO |

|

When noncardiac surgery is required in patients currently taking a P2Y12 inhibitor, a consensus decision among treating clinicians as to the relative risks of surgery and discontinuation or continuation of antiplatelet therapy can be useful. |

IIa / C-EO |

|

Elective noncardiac surgery after DES implantation in patients for whom P2Y12 inhibitor therapy will need to be discontinued may be considered after 3 months if the risk of further delay of surgery is greater than the expected risks of stent thrombosis. |

IIb / C-EO |

|

Elective noncardiac surgery should not be performed within 30 days after BMS implantation or within 3 months after DES implantation in patients in whom DAPT will need to be discontinued perioperatively |

III: HARM / |

|

*Level of Evidence. Class I (Strong): Benefit >>> Risk. Class IIa (Moderate): Benefit >> Risk. Class IIb (Weak): Benefit ≥ Risk. Class III: Benefit = Risk. |

|

ACC/ AHA Advice on Elective Non-Cardiac Surgery in Patients on Dual Antiplatelet Therapy

- “Risk of stent related thrombotic complications is highest in the first 4-6 weeks after stent implantation but continues to be elevated at least 1 year after DES placement.

- The time frame of increased risk of stent thrombosis is on the order of 6 months, irrespective of the stent type (BMS or DES).

- If P2Y12 Inhibitor therapy needs to be held in patients being treated with DAPT after stent implantation, continuation of aspirin therapy if possible is recommended.

- If a P2Y12 inhibitor has been held before a surgical procedure, therapy should be restarted as soon as possible, given the substantial thrombotic hazard associated with lack of platelet inhibition early after surgery in patients with recent stent implantation.”

ACC/ AHA Treatment Algorhythm for the Timing of Noncardiac Surgery in Patients with Coronary Stents

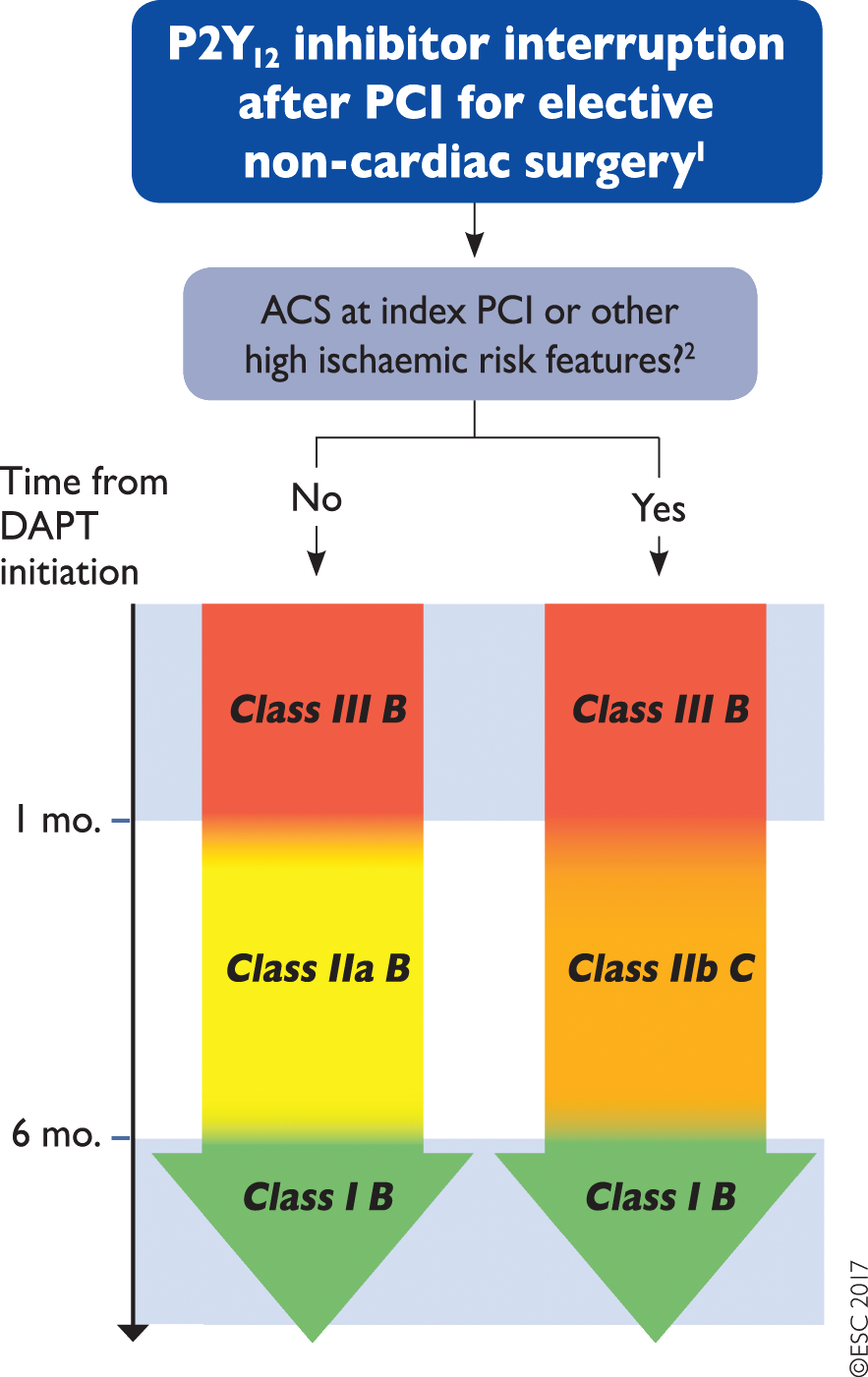

ESC Recommendations on DAPT in NCS (2017)

ESC Recommendations on DAPT in NCS (2017)32

|

Recommendation |

LOE* |

|

Continue aspirin perioperatively if the bleeding risk allows, and to resume the recommended antiplatelet therapy as soon as possible post-operatively |

I / B |

|

After coronary stent implantation, elective surgery requiring discontinuation of the P2Y12 inhibitor should be considered after 1 month, irrespective of the stent type, if aspirin can be maintained throughout the perioperative period. |

IIa / B |

|

Discontinuation of P2Y12 inhibitors should be considered at least 3 days before surgery for ticagrelor, at least 5 days for clopidogrel, and at least 7 days for prasugrel |

IIa / B |

|

In patients with recent MI or other high ischaemic risk features requiring DAPT, elective surgery may be postponed for up to 6 months |

II / B |

|

If both oral antiplatelet agents have to be discontinued perioperatively, a bridging strategy with intravenous antiplatelet agents may be considered, especially if surgery has to be performed within 1 month after stent implantation |

IIb / C |

|

It is not recommended to discontinue DAPT within the first month of treatment in patients undergoing elective non-cardiac surgery |

III / C |

|

*Level Of Evidence. Class I: Evidence/ General agreement that Treatment Beneficial. Class IIa: Weight of Evidence in Favour of Treatment. Class IIb: Usefulness is less well established by Evidence/ Opinion. Class III: Evidence/ General Agreement Treatment Not Beneficial and may be harmful. |

|

Summary of ESC Recommendations of Timing of NCS After PCI

*24/7 Cath Lab facilities should be available if within 6 months of PCI

ESC Advice on Elective Non-Cardiac Surgery in Patients on Dual Antiplatelet Therapy

- “In surgical procedures with a low bleeding risk, every effort should be made not to discontinue DAPT perioperatively.

- In procedures with a moderate bleeding risk, patients should be maintained on aspirin while P2Y12 inhibitor therapy should be discontinued whenever possible.

- Postpone elective non-cardiac surgery until completion of the full course of DAPT. In most clinical situations, aspirin provides benefit that that outweighs the bleeding risk and should be continued. Possible exceptions to this recommendation include TURP, intraocular procedures and operations with extremely high bleeding risk.

- A minimum of 1 month of DAPT should be considered, independently of the type of implanted stent (BMS or current generation DES).

- In patients at high ischaemic risk due to ACS presentation or complex coronary revascularisation procedure, delaying surgery up to 6 months after index ACS or PCI may be reasonable.”

Aspirin for Secondary Prevention of Stroke

American Stroke Association guidelines recommend lifelong aspirin (or anticoagulation) for patients with a history of stroke33. Perioperatively the picture is less clear.

A 2018 systemic review and meta-analysis34 of aspirin use in the perioperative period failed to demonstrate a reduction in stroke or TIA risk.

Of ~14000 patients included in the metaanalysis, ~8500 came from the PEP Trial35, assessing aspirin for VTE prevention in patients suffering hip fracture (average age 79). Patients were randomised to aspirin or placebo, with no significant difference in stroke rates between the two arms demonstrated.

POISE-2 36 was the source of most of the remaining meta-analysis patients (~5000). Patients at increased cardiovascular risk were randomized to aspirin or placebo and stratified into those not already on aspirin (initiation stratum) and those already on aspirin (continuation stratum). A reduction in stroke rate was seen in the initiation stratum (0.1% vs 0.4%, RR 25%, NNT 314, p 0.03), but no significant difference was seen in the continuation stratum (p 0.19).

It’s also worth noting that POISE-2 only counted stroke as defined by new focal neurological signs or symptoms lasting longer than 24 hours. The NeuroVISION trial37 detected asymptomatic strokes in 7% of studied patients (all over 65), thus perioperative subclinical stroke risk may be underestimated..

The risk (and clinical implications) of perioperative stroke must be weighed against the risk and clinical implications of bleeding on individual patient and procedure basis. More on perioperative assessment of stroke risk is available here.

References

- Endothelialization of Drug Eluting Stents and its Impact on Dual Anti-platelet Therapy Duration - Pharmacol Res 2015

- Functionally Incomplete Re-Endothelialisation of Stents and Neoatherosclerosis - JACC 2017

- A Comprehensive Update On Aspirin Management During Noncardiac Surgery 2020

- One-year Results of a Factorial Randomized Trial of Aspirin vs Placebo and Clonidine vs Placebo in Patients Having Noncardiac Surgery - Anesthesiology 2020

- 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease - Circulation 2019

- Effects of Meloxicam on Platelet Function in Healthy Adults - J Clin Pharmacol 2002

- Aspirin in Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery - POISE-2 - NEJM 2014

- Effect of aspirin in vascular surgery in patients from a randomized clinical trial - POISE-2 - BJS 2018

- Low-dose and high-dose acetylsalicylic acid for patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy - RCT - Lancet 1999

- Dual antiplatelet therapy reduces stroke but increases bleeding at the time of carotid endarterectomy - J Vasc Surg 2016

- Rationale and design of the POISE-2 Trial - Am J Heart 2014

- One-year Results of a Factorial Randomized Trial of Aspirin vs Placebo and Clonidine vs Placebo in Patients Having Noncardiac Surgery - Anesthesiology 2020

- Timing of Surg after BMS and DES - AJC 2009

- Perioperative Cardiovascular Risk of Prior Coronary Stent Implantation Among Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery - JACC 2016

- Prevention of Premature Discontinuation of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients with Coronary Artery Stents - JACC 2007

- UpToDate - Clinical use of intracoronary bare metal stents - Last Update 16-12-2020

- 2017 ESC focused update on DAPT in CAD Developed In Collaboration with EACTS - European Heart Journal 2018

- ref:13

- Management of antiplatelet therapy in patients with Coronary Stents Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery - Association with Adverse Events - BJA 2018

- Timing of Noncardiac Surgery Coronary Artery Stenting With Bare Metal or Drug-Eluting Stents - AJC 2009

- 2016 ACC-AHA Guideline Focused Update on Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease - JACC 2016

- Previous Coronary Stent Implantation and Cardiac Events in Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery - Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2010

- Timing of Surgery After Bare Metal Stents and Drug Eluting Stents - AJC 2009

- Risk Associated With Surgery Within 12 Months After Coronary Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation - JACC 2016

- ref:16

- Risk of Elective Major Noncardiac Surgery After Coronary Stent Inserion - Circulation 2012

- ref:13

- ref:20

- ref:6

- Patterns of Antiplatelet Therapy During Noncardiac Surgery in Patients with Second Generation DES - J Am Heart Assoc 2020

- ref:21

- ref:17

- AHA - ASA - Guidelines for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients with Stroke and Transient Ischaemic Attack - Stroke 2014

- Perioperative Aspirin Therapy in non-cardiac surgery - a systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials - Int J Card 2018

- Prevention of Pulmonary Embolism and Deep Vein Thrombosis with Low Dose Aspirin - PEP Trial - Lancet 2000

- ref:6

- Perioperative covert stroke in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery - NeuroVISION - Lancet 2019

- Aspirin In Patients With Previous Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery - Annals Int Med 2018

- Perioperative Management of APT in Pts w Coronary Stents - Italian Consensus Document - Eurointervention 2014

- Perioperative Management of Antiplatelet Therapy in Noncardiac Surgery - Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2020

- Periprocedural antithrombotic management for lumbar puncture - Association of British Neurologists clinical guideline - BMJ 2018

- A Comprehensive Update On Aspirin Management During Noncardiac Surgery 2020

- UpToDate - Clinical use of intracoronary bare metal stents - Last Update 16-12-2020

- Incomplete Revascularization Is Associated With an Increased Risk for Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events Among Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery - JACC 2017

- A Comprehensive Update On Aspirin Management During Noncardiac Surgery 2020

- Use of Antiplatelet Therapy/DAPT for Post-PCI Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery - JACC 2017

- Use of Antiplatelet Therapy/DAPT for Post-PCI Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery - JACC 2017