Search POM Topics

-

Crisis

-

General

-

Perioperative Medication Management

-

Investigations

-

Calculators

-

Cardiology

-

Complications

-

Day Surgery

-

Endocine

-

Haematology

-

Neurology

-

Paediatrics

-

Pain

-

Respiratory

-

Useful Links

Cardiovascular Risk Assessment

ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery

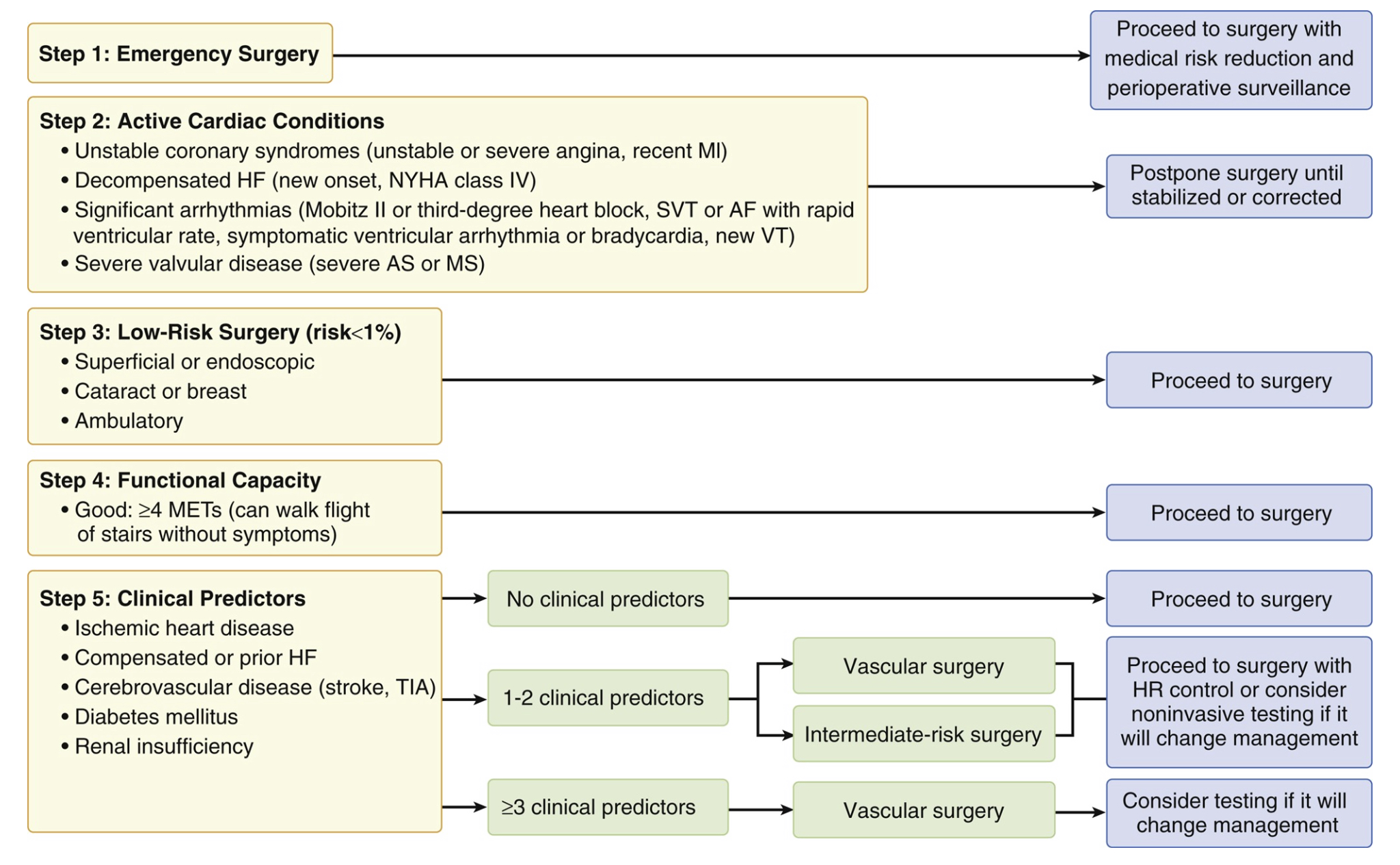

ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery16

This recommendation is now replaced by the 2014 pathway, but has been included as it’s still often referred to.

|

Surgical Cardiac Risk Stratification by Surgery Type17 |

||

|

Low Risk (<1%) |

Intermediate Risk (1-5%) |

High Risk (>5%) |

|

|

|

|

Surgical Cardiac Risk Stratification by Surgery Type18 |

|

Low Risk (<1%) |

|

|

Intermediate Risk (1-5%) |

|

|

High Risk (>5%) |

|

|

Revised Cardiac Risk Index Criteria |

|

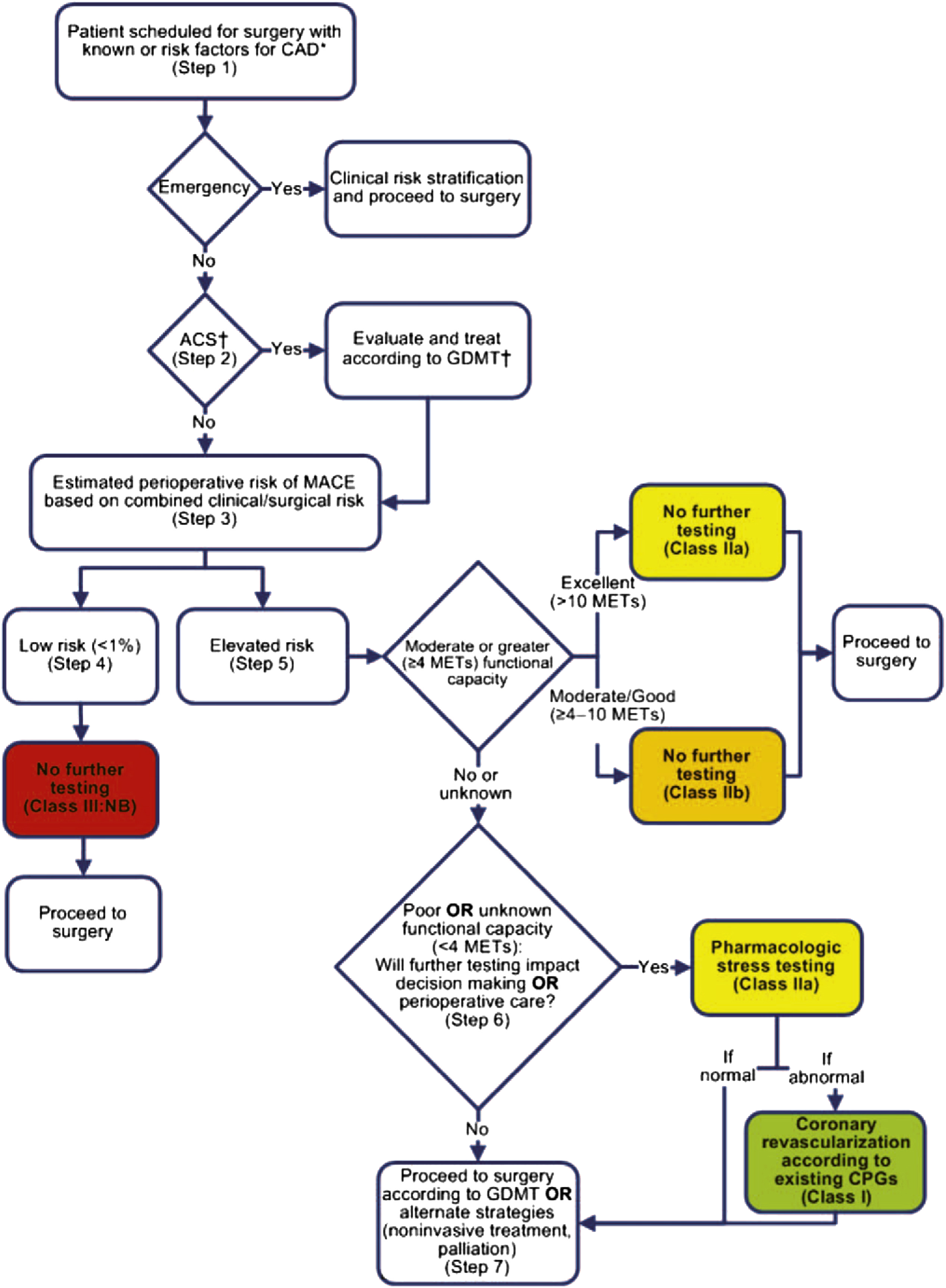

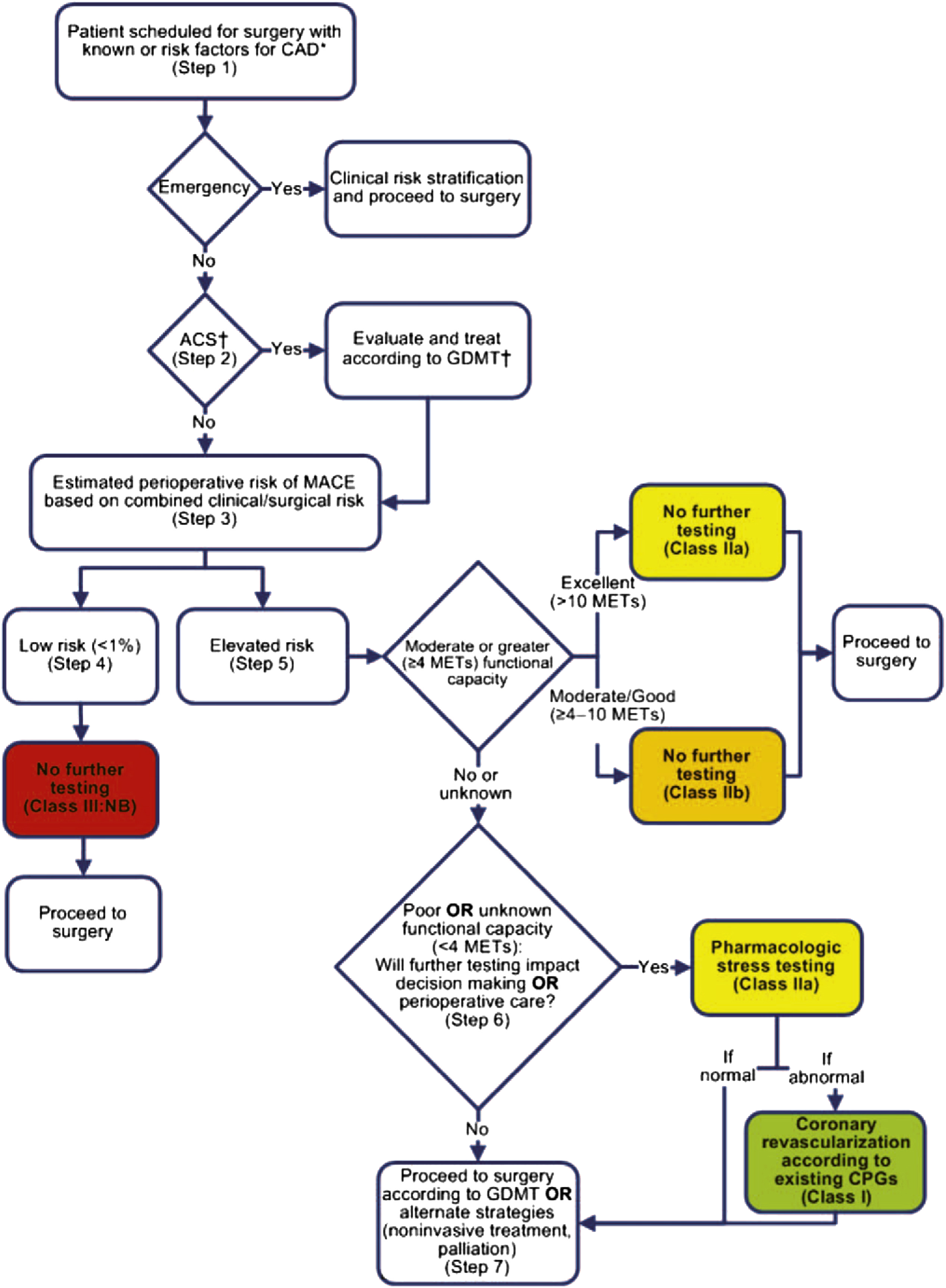

ACC/AHA 2014 Guideline on Perioperative CardiovascularEvaluation and Management of Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery

ACC/AHA 2014 Guideline on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Management of Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery19

Step 1: In patients scheduled for surgery with risk factors for or known CAD, determine the urgency of surgery. If an emergency, then determine the clinical risk factors that may influence perioperative management and proceed to surgery with appropriate monitoring and management strategies based on the clinical assessment.

Step 2: If the surgery is urgent or elective, determine if the patient has an ACS. If yes, then refer patient for cardiology evaluation and management.

Step 3: If the patient has risk factors for stable CAD, then estimate the perioperative risk of MACE on the basis of the combined clinical/surgical risk.

Step 4: If the patient has a low risk of MACE (<1%), then no further testing is needed, and the patient may proceed to surgery.

Step 5: If the patient is at elevated risk of MACE, then determine functional capacity with an objective measure or scale such as the DASI. If the patient has moderate, good, or excellent functional capacity (≥4 METs), then proceed to surgery without further evaluation.

Step 6: If the patient has poor (<4 METs) or unknown functional capacity, consider whether further testing will impact management. If yes, then pharmacological stress testing is appropriate. If abnormal, consider coronary angiography and revascularization depending on the extent of the abnormal test.

Step 7: If testing will not impact decision making or care, then proceed to surgery.

Exercise Tolerance

AHA and ESC Guidelines 1,2 include exercise tolerance consideration in pre-operative cardiac risk assessment, defining poor exercise tolerance as an inability to maintain 4 or more Metabolic Equivalent Tasks (METs). Poor exercise capacity predicts post-operative cardiac and respiratory complications3,4,5, but is probably more indicative of pulmonary risk than cardiac risk6. Consistent with this, CPET measured peak oxygen consumption in the METS study predicted pulmonary complications, ICU admissions and wound infection, but not cardiac complications7.

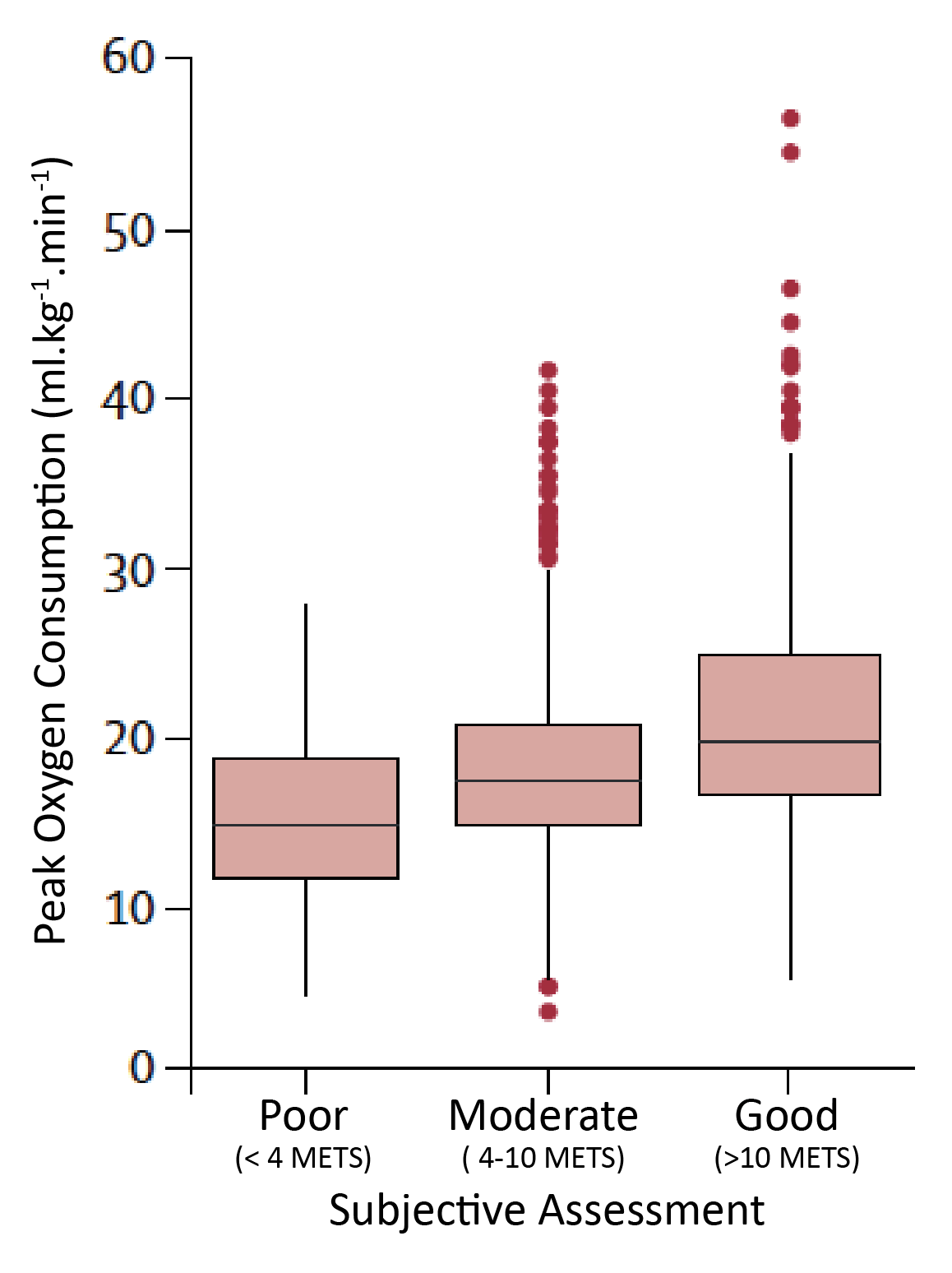

Subjective assessment of exercise tolerance is unreliable. In the 2018 METS study 8, subjective anaesthetist assessment correctly identified less than one-fifth of patients with poor exercise tolerance and did not predict cardiac complications. The authors concluded that subjective functional capacity should not be relied on, recommending instead the Duke Activity Status Index (DASI)9,10, which did predict cardiac complications, despite only a moderate correlation with peak oxygen uptake.

ACC/AHA guidelines specify that a standardised objective measure such as the DASI should be used to assess functional capacity. The DASI may actually provide a broader assessment of function than aerobic fitness alone, via the impact of non-aerobic factors such as musculoskeletal strength and frailty.

Overall, exercise tolerance provides a practical integrated assessment of functional reserve, but may be limited in its ability to predict sporadic events like myocardial infarctions and a ‘poor exercise tolerance’ requires assessment to establish the cause and perioperative implications.

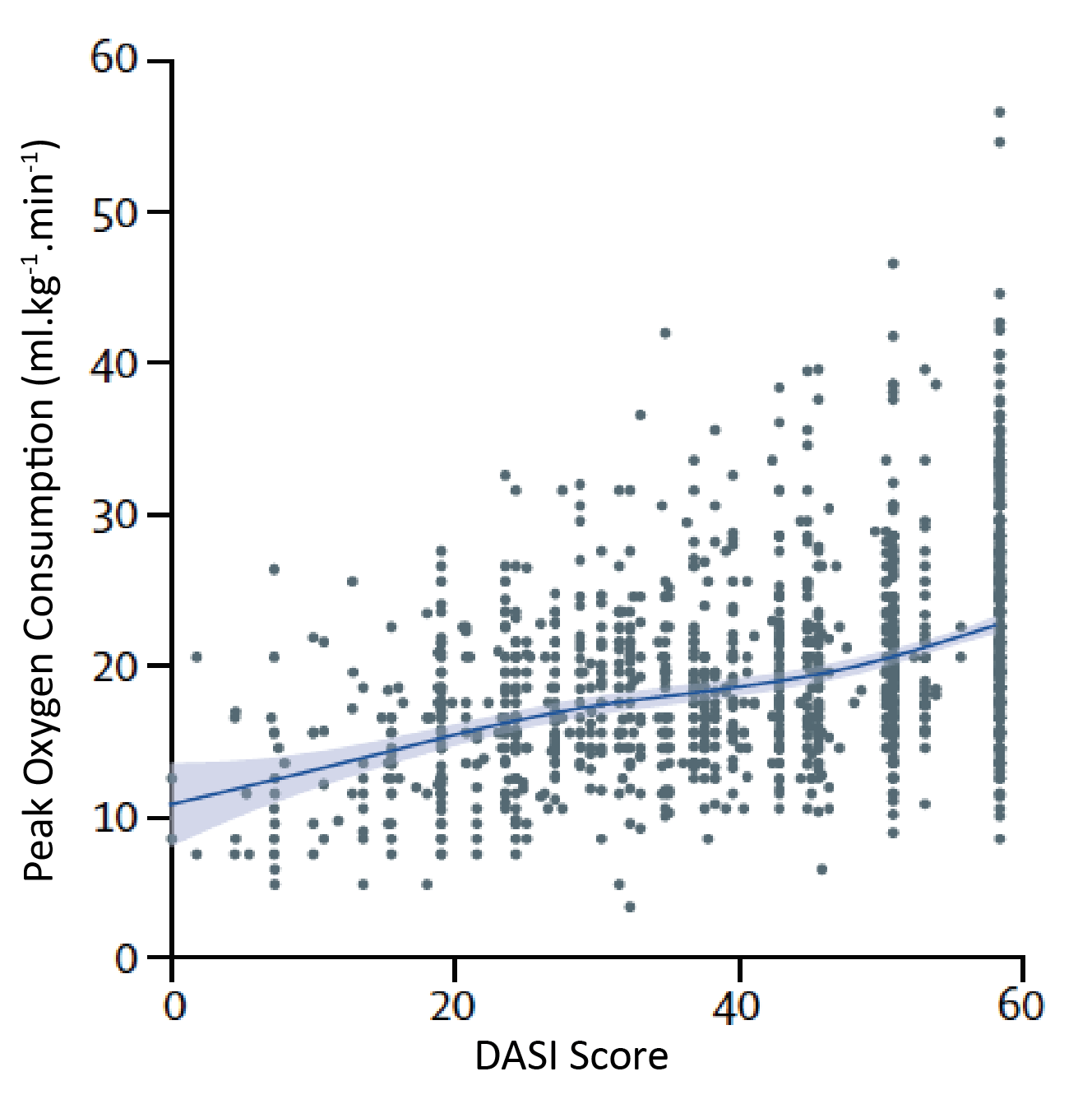

Correlation between Subjective Assessment and DASI Scores with CPET Assessed Peak Oxygen Uptake in the METS Study 20

CPET Peak Oxygen Consumption in Patients Vs Subjectively Assessment of Exercise Capacity

CPET Peak Oxygen Consumption in Patients vs DASI Score

4 METS equates to a peak oxygen consumption of 14ml.kg-1.min-1.

A DASI Score of 10 equate to an exercise capacity of around 4 METS

Scores were shown to be predictive of perioperative cardiac complications and death.

Examples of Metabolic Equivalence of Common Activities

A Comprehensive Reference on Metabolic Equivalence of various tasks can be found here.

Cardiac Risk Prediction Tools

Lee’s Revised Cardiac Risk Index (1999)11 is easy to calculate and simple to apply. Its age may make it less applicable in the setting of modern IHD and perioperative management.

The MICA (GUPTA) model12 uses data from the 2007 NSQIP data set and quantifies individual risk for MI or cardiac arrest out to 30 days post-op. A model focusing on geriatric patients (over 65 years old) was published in 201713.

A model designed to assess post-operative myocardial infarction risk in the 30 days following vascular surgery has been published by the Vascular Quality Initiative, using 2012-2014 data from the VQI registry14. Vascular procedure specific prediction tools with modestly further improved accuracy have been developed for carotid endarterectomy, EVAR, infra-inguinal bypass, supra-inguinal bypass and open AAA repair.

The ACS-NSQIP calculator provides an estimation of a range of perioperative complications and is available through an online calculator.

A comparison15 of the above calculators found that all were useful in identifying low-risk patients who did not require further testing, but he MICA (GUPTA) calculator may be most reliable in identifying higher risk patients.

Calculators

|

Revised Cardiac Risk Index Criteria |

|

Open ACS-NSQIP Calculator in new tab.

References

- ref:2

- ref:4

- The Prognostic Value of Exercise Capacity - A Review of the Literature - AM Heart J 1991

- Symptom-Limited Stair Climbing as a Predictor of Postoperative Cardiopulmonary Complications After High-Risk Surgery - Chest 2001

- Relationship between the inability to climb two flights of stairs and outcome after major non-cardiac surgery- implications for the pre-operative assessment of functional capacity - Anaesthesia 2005

- Activities of Daily Living and Cardiovascular Complications Following Elective, Noncardiac Surgery - Yale J of Biology and Medicine 2001

- Assessment of functional capacity before major non-cardiac surgery - METS Study - Lancet 2018

- ref:11

- A Brief Self-Administered Questionnaire to Determine Functional Capacity - The Duke Activity Status Index - Am J Cardiol 1989

- Duke Activity Status Index for Cardiovascular Diseases- Validation of the Portuguese Translation - Arq Bras Cardiol 2014

- Derivation and Prospective Validation of a Simple Index for Prediction of Cardiac Risk of Major Noncardiac Surgery - Circulation 1999

- Development and Validation of a Risk Calculator for Prediction of Cardiac Risk After Surgery – GUPTA – Circulation 2011

- Derivation and Validation of a Geriatric-Sensitive Perioperative Cardiac Risk Index – J AM Heart Assoc 2017

- The Vascular Quality Initiative Cardiac Risk Index for prediction of myocardial infarction after vascular surgery - Journal of Vascular Surgery 2016

- Comparison of 4 Cardiac Risk Calculators in Predicting Postoperative Cardiac Complications After Noncardiac Operations - Cardiol 2018

- ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery - JACC 2007

- 2014 ESC-ESA Guidelines on non-cardiac surgery- cardiovascular assessment and management - European Heart Journal 2014

- 2014 ESC-ESA Guidelines on non-cardiac surgery- cardiovascular assessment and management - European Heart Journal 2014

- 2014 ACC/AHA Guideline on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Management of Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery - JACC 2014

- ref:11

- Perioperative Cardiovascular Risk Assessment And Management For Noncardiac Surgery A Review - JAMA 2020

- Perioperative cardiac events in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery- a review of the magnitude of the problem, the pathophysiology of the events and methods to estimate and communicate risk - CMAJ 2005

- Preoperative Cardiac Risk Assessment - Mayo Clin Proc 2020

- Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiac Risk Assessment and Management for Patients who Undergo Noncardiac Surgery - Canadian Journal of Cardiology 2017

- Risk of Surgery Following Recent Myocardial Infarction - Annals of Surgery 2011